It is necessary to fail gracefully. We fail more often than we succeed. Despite ample opportunities for practice, it never gets easier.

Donald Duck is his own worst enemy. He rarely wins, and when he does it’s usually accompanied by a poison pill, a humiliation or setback. He fails not because he’s incapable but because he can’t overcome his worst impulses: wrath, envy, pride, greed, sloth. He looks for shortcuts and hamstrings himself out of spite.

The reason why Donald remains compelling is that he’s simultaneously both protagonist and antagonist. When faced with the choice between right and want, he deliberates. This has been part of Donald’s character from the very beginning. 1938’s “Donald’s Better Self” literalizes this conflict by putting Donald in the position of having to choose between a devil and an angel, perched one on each shoulder. Given the choice between selfishness and selflessness, he doesn’t always do the right thing. Placed into the position of being a reactive agent – such as for most of the longer adventure stories in the comics – he usually does, and enjoys the occasional happy ending. In the shorter 10-page features he stumbles because his motivations as a protagonist are self-defeating.

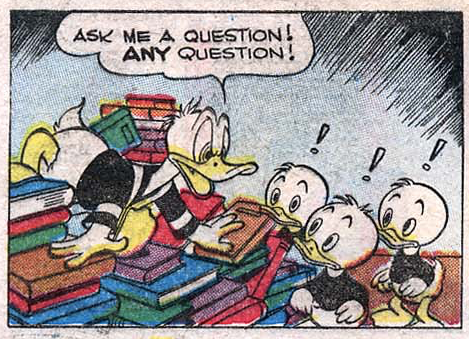

“The Crazy Quiz Show” first appeared in Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories #99 in 1948. The story, from Donald’s perspective, is a crushing defeat. He studies hard for the purpose of winning a travelling quiz show, stuffing his head with trivia. Certain of his victory, he antagonizes the hosts. They ensure he loses the competition, awarding prizes not to qualified contestants but his own nephews as they answer ludicrously simple questions.

Donald’s problem is that no matter how well he stuffs his head with facts, he can’t escape his own pettiness. This pettiness reveals itself in his actions. He refuses to wait in line. He refuses to accept the rules of the game. He refuses to lose with dignity.

He also refuses to acknowledge that his plan is flawed. He spends all his money on books to study for the quiz, certain that his investment will be returned when he is victorious. It’s a get-rich-quick scheme that hinges on him learning a great deal of information in a short amount of time – a shortcut that seems significantly more elaborate than getting a better job. (This is still 1948, though, so every person reading the story regardless of age would recognize the backdrop of postwar privation against which Donald’s quest for sudden riches becomes significant.)

Donald is undone by arrogance. “I hate to brag,” he boasts, “but I know the answers to just about everything!” It’s at this moment that the reader realizes that the conflict is not Donald in opposition to the quiz show, but Donald’s basest motives at war with his best. Our sympathy for the Duck disappears. He deserves what he gets.

*

We undervalue our gifts.

It’s easy to do this because the world tells us that we should. It’s difficult to keep faith in yourself. I’m a writer, or at least, that’s what I’ve often fancied myself. I didn’t start out as a very good writer, which is standard. I wrote a lot of shit, and that’s how it works. I wrote one completely terrible book that no one read. I wrote another slightly less terrible but only because the first book was so completely awful book. And finally I lit upon a decent idea, and a decent enough voice, and ran with it, far enough to produce a third, only partially terrible book.

Now there was a sense of accomplishment! It only took six years to write something not completely awful. It was the fruit of the most prolific period of my life, when I was producing a significant amount of content for both The Hurting and Popmatters, working for that site as a copyeditor, as well as the occasional piece for the Journal.

Here’s a secret about being a writer: you can’t be a writer unless you have something to write about. It’s fine to want to be a writer but without a subject a writer is useless. A writer only finds a subject by living long enough to separate the wheat of their experiences from the chaff. You have to read millions of words and write a few million yourself. Somewhere in the middle of all that reading and writing and living your voice appears and announces your topic.

Looking back on my career I focus on the long periods of languor, inactive stretches without any substantive work. After finishing my third book in 2006 I tried to sell it. That consumed most of the mental energy previously spent on writing. The significant difference is that the reward for writing is often the quality of the writing itself, while the reward for trying to sell a book needs to be selling a book. I did not succeed in selling a book.

In hindsight, it is good that I did not succeed in selling a book.

The problem is that not selling the book was a blow. I had correspondence with dozens of agents, some of whom expressed interest and read the first chapters, a couple of whom even read the manuscript. I got good feedback. I heard a few variations on, “I love it, but . . .” Nothing led to a sale, nothing led to an agent, nothing really led anywhere. I worked my way down every figure in the US publishing industry and a few in the UK, until I could find no more names to contact. Everyone to whom I could show the book given my limited vantage point on publishing at the time, I did.

I would be embarrassed now if the book had been published. I thought it was about a few things – 9/11, mental illness, conspiracy theories – when really it was about one thing: being angry at my ex-wife. I was angry at the world for having left me in the position of living alone in central Massachusetts, working a dead end job that managed to be both unpleasant and unsettling. Anyone reading the book would be justified in wondering after the state of my mental health – one person close to me said it was a genuinely upsetting story told in a voice that was recognizably mine. Not the wished-for reaction.

Failing to sell the manuscript took the wind out of my sails. It was a blessing that the book floundered, but at the time it was a significant blow. Playing around with another idea I produced a few thousand words about a man stuck in a hospital bed after almost dying in a car crash. He was really upset about his divorce, however. When I realized that was the direction in which my ideas were naturally trending, I put it up and never went back.

The only charm my terrible job had was that on most nights I was left to my own devices for the entirety of the shift – free to read, write, sometimes watch TV. Most of my knowledge of foreign film comes from this period – back when Netflix was still primarily a DVD rental company. I read Jane Eyre and Jane Austin, polished off the Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy series in a quick two days and spent a leisurely week on The Book of the New Sun.

But it wasn’t the kind of job that people kept. It was an easy job to get and a hard position to fill because the demands were significant and not readily apparent. The facility was set in the heart of central Massachusetts, tucked among rolling hills and ancient lanes. Most nights were quiet. But the clients were erratic – older kids and teens with mental illness, developmental disabilities, behavioral problems, or substance abuse issues. Often many at once. A lifetime’s experience dealing with mental illness and being around mentally ill people gives me an unusual degree of compassion for people in that situation. Regardless of how kind and understanding they may appear, many “normal” people do not have the patience for dealing with misfiring brains. I have nothing but patience for anyone who knows how to lose an internal battle.

*

We can’t really root against Donald but it is difficult to root for him. His life can be reduced to a series of morality plays, with the curtain often falling only at the moment of his most severe humiliation. Hubris breaks him.

For Donald the worst possible humiliation comes in the form of his own nephews. “The Crazy Quiz Show” presents Huey, Dewey, and Louie at a relatively early place in their development, before they become impossibly smart thanks to the introduction of the Junior Woodchucks and their eponymous Guidebook. They’re still just kids here, and young. Even given that, their ability to confound their uncle’s best-laid plans remains formidable.

You know you’re reading Carl Barks when you see Donald dressing down his nephews with the pejorative “Infants!” It’s a verbal tic you don’t see outside of Barks’ stories, because Barks’ Donald is a significantly different creature than later versions. In their contemporary incarnations the Disney mainstays – Donald, of course, Mickey, Goofy and the rest – are grown children, waddling through life with the deathless bonhomie of corporate mascots on an eternal sunset cruise. Barks’ Donald is very angry, and not simply because he has a temper. He rails against his nephews, against his uncle, against the world. He is condescending, rude, and dismissive even of his friends and family. (It should be noted that he appears to have few of the former and is only tolerated by most of the latter.) He has a monstrous ego and failure only ever emboldens him to double-down on his mistakes.

The effect of reading Donald Duck on the page is significantly different from watching him in a cartoon. Comics are silent, so Donald’s particular speech impediment is not represented. There is no indication that Donald in these stories sounds different from anyone else. This is important because the dialogue in these comics depends on a crisp, clipped delivery more similar to something you’d hear in a George Cukor comedy than a Silly Symphony. You cannot imagine Clarence Nash’s quack delivering these lines coherently.

Without his cartoonish speech impediment, he seems less like a talking duck and more like a person who just happens to be a duck. This is a world very much like our own. The rules of nemesis remain firmly in place, ready to smite any mortal who oversteps their boundaries. Barks’ world isn’t a world where everything naturally turns out for the best. It’s a world where hustlers, con men, and crooks lurk around every corner, ready to take advantage of anyone unlucky enough to believe the game isn’trigged.

In Donald’s case, his nephews can usually be found at or near the site of his greatest defeats. Sometimes they purposefully set out to stymy him, sometimes it happens by chance. In this case, when Donald rushes the stage to be the first contestant, the boys have already beaten him there. The quiz show hosts are more than happy to give the boys the chance to upstage Donald, the “professional prize-grabber.” His first question is, “how many killowatts in a freedoffagraph?” Donald scratches his head and asks, “what’s a freedoffagraph?” A gong sounds somewhere off-panel and one of the hosts rushes to squeeze a grapefruit over Donald’s dead. “You’ve got to take the punishment!” he yells as he clobbers Donald with a wet “SKIVSH.”

After this the hosts turn to one of the nephews (it’s often unclear which is which in these stories, but it matters little as the boys have no independent personalities) and gives him a slightly easier question: “How many tails does a dog have?” Under the hot klieg lights he quails, and question marks appear over his head. Donald rushes the stage to help before being pulled away but the nephew is still unable to answer – finally he stammers, “Depends on the dog!” Little beads of sweat pop off his head. But this is sufficient. The host exclaims “Good enough!” and gives the nephew a shiny new bicycle.

The same pattern repeats twice more, once for each nephew. The second question Donald receives is, “What is Mickey Mouse’s Social Security number?” Of course he doesn’t know, but the next question asked of a nephew is, “How many eggs in a dozen eggs?” He can’t quite figure it out. Donald rushes the stage again, but is imprisoned in a barrel-sized block of gelatin. The nephew finally figures out the answer, through luck. (Incidentally, Mickey does actually have a Social Security number: 746-55-2769.)

The final question for the nephews is, “What is two minus two?” The nephew struggles mightily for an entire page as Donald strives to free himself from his Jell-O prison. But the nephew, unable to muster an answer, simply stares blankly, unable to reason the answer. The host finally responds, “You said nothing! The answer happens to be nothing! You win!”

Whereas the first nephew is simply given the bike, the second and third nephews are offered the choice between accepting a bike and accepting money. Being little boys, they choose the bikes and ride them offstage smiling. Donald, as one might expect, reacts poorly.

Finally, Donald escapes his trap and is given one more chance to answer a question, his fourth and final question for all the money in a giant barrel: “How many drops of water pass over Niagra Falls in a week?” But this is an answer Donald knows, so surely – the reader thinks, if only for a moment – his victory is assured.

*

I didn’t get into grad school the first time and it was my own fault.

I barely got into grad school the second time and in hindsight I was very lucky.

Graduate school applications are complex because they represent the first hurdle. In order to jump that hurdle you need a lot of time and money. Although there are ways to sidestep the latter, they are very difficult and mean more of an investment of the former.

After I returned to school in 2007 it became clear that this was a milieu in which I could survive and even prosper. Within a set of rigid parameters academia is fairly easy to navigate. You’re left to your own devices most of the time but are expected to perform your knowledge periodically in order to continue on the same path. I fit perfectly because temperamentally I much prefer to be left to my own devices. The problem comes with the expectations of performance.

Performance is a loaded word. Growing up trans without knowing I was trans placed me in a very difficult position in regards to masculinity: I was repulsed by it, completely alienated and even physically frightened, and yet lacked the vocabulary to describe or even the awareness with which to articulate my experience. Our media – our world – is defined by the reverence paid to masculinity. Sports, music, movies - every field defines the roles of several different masculine spheres into which male-presenting persons must fit themselves or risk being lost. Without masculinity a man is nothing. Powerless men are dangerous men.

I couldn’t handle sports, and felt little kinship with the men on movie screens or staring back at me from album covers. What did I have left? Certainly not fictional men in comic books, who were better than men could ever be in real life because they always made the right choices. You could learn ethics and civics from Captain America but what can a fictional character tell you about how to live when you hate yourself?

So I gathered what role models I could, even if I wasn’t aware of it at the time. I went through a Jack Lemmon phase when I was younger because he seemed to represent a vision of masculinity that wasn’t about striving towards victory but living with defeat. He specialized in playing broken men who somehow found the courage to keep going when by all rights no one could have blamed them for giving up. The secret to understanding his career is that his most famous roles were all essentially the same person placed in different situations. The passive C. C. Baxter in The Apartment and the self-destructive Joe Clay in Days of Wine and Roses are the same man – harried, beaten, but funny, trying very much to hold onto what little dignity was allowed them under the circumstances. They’re both cut from the same cloth as the more comedic Ensign Pulver in Mister Roberts, or Jerry in Some Like It Hot: sometimes you laugh, sometimes you don’t, but there’s always the same guy at the center of it all, covered in flop-sweat and five minutes behind everyone else.

Lemmon’s career culminates in 1973’s unfairly forgotten Save the Tiger. He won an Oscar for the role – fittingly, he won two in his life, one for this dramatic role and one for the comedic Mister Roberts. Same character in different clothes. Save the Tiger is about a washed-out businessman named Harry Stoner who decides the only way to save his business is by hiring someone to burn it to the ground. It’s a rough movie that occasionally veers into the maudlin but it’s an honest story about the ways society lies to men about masculinity. It hurts to wake up one morning and realize that the sense of invincibility you felt as a kid has completely disappeared, only to be replaced with . . . nothing.

My successes in academia are hard-fought but always transitory. Everything I win slips through my fingers. I can’t hold onto it. I have no follow-through. Whatever I do, I always end up like Harry Stoner walking down the sidewalk in Los Angeles, dressed in the most expensive cheap suit imaginable and mulling over the fact that I lost my way and don’t know how to retrace my steps to get back.

The reason I didn’t get into grad school the first time is quite simple. I was sabotaged by a professor who developed a dislike for me but lied to my face that he would support me. In hindsight it’s not hard to figure out why. He was an old, petty son of a bitch and I had a strange, subtle fear of men in positions of authority that made it difficult to keep up my side of any professional relationship. Still does, to an extent.

I only found this out later in the spring after I had received rejection notices from fourteen out of fifteen schools to which I had applied. I wrote a letter to the fifteenth program begging to hear an answer because it was the only hope still outstanding. To my eternal surprise the head of the department wrote me back a long letter saying, in essence, yours was a promising application but you need to get better recommenders. When he told me that, it suddenly made sense. I had been double-crossed.

Still, the message was encouraging. I didn’t throw in the towel. I knew I could do better, so I did. I retook the tests to improve my scores. The next year I applied to a wider spread of programs, had better letter writers, and got into a few. The last school I had heard from the previous year – where the department head wrote me the very long, gracious, and helpful letter – turned out to be UC Davis, where I am today.

*

Donald wants the same things everyone else does, but he never quite makes it because he wants it too much. He doesn’t get that in a world sharply split between suckers and sharpies, the worst suckers are those who fancy themselves sharpies.

Why does Donald fail? He has to fail. He falls short because the virtues needed for success in Barks’ universe are forever out of his reach. Patience and hard work are alien concepts. Donald’s Uncle Scrooge, introduced a year before “The Crazy Quiz Show,” quickly outgrew his original purpose as a foil for his wastrel nephew. Despite his mania for money, Scrooge was also a model for the precisely the kind of behaviors that Barks was keen to show Donald lacked. He was smart, but he was also diligent, forthright, and above all respectful of an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay. (His idea of an honest day’s pay was tantamount to indentured servitude, but it’s not as if Donald is ever doing anything else.) Donald is always trying to figure out a way around having to do the hard work of working hard, and becomes frustrated when his shortcuts invariably fall short.

Here’s his chance, though. He knows full well how many drops of water pass over Niagara Falls. This was in Volume IV of Electro-Kinetic Science! Victory is within his grasp. All he needs to do is get through the answer. The very long answer.

Donald should be exultant. He’s won: he’s beaten the con men at their own game. He pulled a miracle out of his back pocket. But the effort destroys him.

There’s something missing in Donald that forces him to take the path of least resistance even when it ends up costing him everything. His nephews win the day not because they are more clever or even more moral than their uncle. They win because they know on some level they’re playing a game. The hosts let them win because they’re little kids on a game show. It’s no fun to see a pro run the table, not when you can upstage him with his own children.

The nephews don’t really care that their uncle is barking mad. They’re used to dealing with such a mercurial authority figure, and the three of them are fairly evenly matched to the one of him. (Donald didn’t always get the upper hand on the kids, but every now and again he did. The very next Donald ten-pager after “The Crazy Quiz Show” was “Truant Officer Donald,” which ends with Donald making the boys attend Saturday detention for being willful brats.) They parade their prizes in front of him as he stews. One nephew exclaims, “Look! No hands!” as he rides by. The next announces, “Look! No feet!” as he rides the bicycle offstage balanced on his head.

At the very end, having stunned the audience with his amazing recitation, Donald is given the same choice as his nephews: take a bike or a barrel of money. A big barrel of money. But he’s been stunned by the effort. “The contestant is dazed from his great mental effort!” exclaims an audience member. “I’ve seen such cases lose all power of reasoning!” Donald chooses the tricycle and rides offstage in imitation of his nephews – “Look! No head!” He has humiliated himself.

What’s the lesson here?

Donald’s mistake would appear to be that he overestimates his own abilities. His greatest sin is overconfidence, and this makes him dangerous to himself. His nephews are instruments of divine retribution: there is nothing he can do that can’t be countered by three small children, and they serve as a natural check on his overweening pride. This is why, incidentally, Donald is usually relegated to a supporting role in later Uncle Scrooge stories. He’s no match for his uncle, and his uncle in turn regards his lazy nephew with a mixture of pity and condescension. His uncle doesn’t always get happy endings either, and when Scrooge falters it’s because he allows his own primary negative character trait – greed – to overcome his natural kindness.

The only truly consistent law of Barks’ moral universe is that you will fail if your intentions are misplaced. His ducks are such wonderful characters because they are motivated by the same desires we recognize in ourselves. We sympathize with Donald because his failures mirror our own. We see him riding the tricycle offstage to the roaring laughter of the audience and the quiz show hosts and we feel sympathy for him. Failure is a familiar sensation, even if – as is also the case in our own lives – we nevertheless recognize the comeuppance as well-deserved.

Barks dismantles Donald in ten pages. We don’t want to see Donald fail but at the same time we do. His travails provide assurance that bad behavior ultimately creates the conditions of its own downfall. The instruments of this downfall may as well be the fates themselves. Crooks are simply a fact of life in Barks’ world, anonymous forces of nature that exist to test the individual’s resolve not against the universe but against themselves. No one brings the hosts to account for their part. It’s rigged but it’s still their game, and Donald’s problems begin with his assumption that the rules will remain consistent and equitable. What he doesn’t understand is that the rules of the contest are subject solely to the whims of the men behind the contest. The only way to effectively win in this situation would be, like his nephews, to accept that the game is rigged and act accordingly. Fair doesn’t enter into the equation.

*

On the morning of 9 December 2014 I failed my Qualifying Exam. The QE is the final exam before the student advances to the level of candidate, and is preceded by the Preliminary Exam. Whereas the latter is designed to test a student’s knowledge of a large breadth of literature in your field, the former is designed by the student themself as a prelude to the writing of their dissertation. You write a prospectus for your project that entails what you will be doing and how you will do it, and then sit in a room for an hour and a half while five faculty members grill you on the details of a book-length scholarly project you haven’t yet written.

It is a grueling experience. Technically I did not “fail.” The official designation was “not pass,” and there’s a world of difference between the two. A failure would have put me in a tight bind, whereas merely not passing allowed me to make the test up in a manner deemed satisfactory by my committee. Thankfully, they agreed to allow me to make up the test by producing half of a first chapter. I wrote half a chapter over the course of the new few months and had no problem passing. I had stacked my committee with faculty who knew me and knew the quality of work I was capable of producing, and I suspect (but will probably never know) that may have saved me.

There are two kinds of failures: those where you know with certainty that you did all you could, and those where you know that you could have done more. The first is vanishingly rare, the second dominates every horizon of our adult lives.

The best example of the first type of failure was my marriage. I have no plans to dig up old bones. It’s a dead subject that holds no interest to me. I am confident after having examined the matter from every angle for many years that not only was the divorce unavoidable but that it should probably have come sooner. I am even more certain that the only reason it lasted as long as it did is that I did everything in my power to make the relationship work. I failed, and it was an inevitable failure, but it’s not one I regret.

My qualifying exam was no such sanguine event. I failed because I wasn’t prepared. I wasn’t prepared despite many months of preparation, preceded by years of study. I walked into the room with a headache from a concussion the previous week but I didn’t want a postponement – even if I could have got one. I was as ready for that test as I could be, which wasn’t much.

I couldn’t concentrate on anything. I couldn’t make myself focus, couldn’t buckle down and read the books and articles I needed to read, couldn’t even bring myself to spend a day revising my terrible prospectus. At a certain point, whether I admitted it to myself at the time, I gave up. I felt at that moment on that December morning as if I had been hollowed out and drained of every rivulet of motivation. I knew what was coming and I walked into the exam room already flinching from an imminent blow.

The exam itself was fairly brisk. After a couple questions it became obvious that I was woefully unprepared. They had already independently concluded that my prospectus was unworkable and proceeded to hammer me on the fact that I refused to give them a straight answer. The problem is that I was trying as hard as I could for over an hour to give them the straight answers they desired. Every time I opened my mouth I kept wandering off topic, thinking in my mind that of course I need to lay groundwork in one idea before I can move on to the next . . . only to be pulled up short. You’re not answering the question. Well, I’m trying, you see, I need to establish – no you need to answer the question. Why can’t you just answer the question.

In the entire running time of the exam I didn’t answer a single question to their satisfaction. Every answer I gave appeared evasive or simply non-sequitur, and eventually my problematic answers became the subject of the test. At that point I knew it was over. They thought I was being equivocal, and I certainly was, but I was trying desperately throughout the running time of the exam to tell them in as simple and unambiguous a way as possible that I was trying my damndest to unkink my answers and give them what they wanted to hear. The harder I tried the more I felt my grip of the situation loosening, until eventually I was just . . . blank. I had no answers. I knew nothing. I was empty.

After a certain point they relented. We took a break and they talked. I knew I wouldn’t be getting a second round of questions. I don’t know what they said but the conversation lasted a while. When I was called back in the five professors explained their terms. They asked if I would accept them. I replied yes. I may have added something to the effect that they would have been completely justified in failing me outright. And they would have.

*

I blamed myself for failing the test. Given what I know now, maybe I shouldn’t be so hard on myself. December 2014 was a year and a half out from the biggest shock of my life. I spent the following eighteen months descending into a state of agonized paralysis, a long dark tunnel with only one outlet. It was shaping to be a harrowing period, and I barely survived.

I didn’t know this at the time. I didn’t know, either, that my concentration and focus issues were most likely not down to a moral failing on my part. I did a good job covering up for decades, developing an entire set of alternate study habits that enabled me to get by without consciously being aware of what I was doing. I spent two decades navigating around a boulder in my brain, unable to see the dimensions of the problem but still dimly aware of the need to adapt to match the pace of my gradually deteriorating concentration. Eventually the deterioration outpaced my ability to cope. This leaves me roughly where I am now at the present moment, unable to focus on reading for more than ten or fifteen minutes at a time. As of this writing I am in need of testing to measure what kind of learning disability I have, as a prelude to any treatment.

I can still write well, as typing focuses my concentration. Typing actually relaxes me, regardless of whether I’m typing an essay or an e-mail or chatting with friends. But I also know that as soon as I finish typing this essay I have to turn around and read it again for the purposes of editing. Copy-editing requires such a high degree of concentration for me that I am only able to do it for very short bursts at a time.

Do you learn from failure? Do you lift yourself up off the mat, wipe the dust off and try again? Or do you wake up the next day and do the same thing over and over again?

Donald is trapped. He can never learn from his mistakes, so his humiliation assumes ritual proportions. You don’t expect him to learn. Any movement he makes is lateral, figuring out a new way to get ahead or get one over, until that too invariably collapses in spectacular failure. He can’t actually learn from his mistakes, however, because that would be the end of his usefulness as a cautionary tale.

Perhaps there’s another world where Donald sees a therapist and gets help for anger management. That guy’s waddling around in a much better headspace now, able to be a much better parent to his nephews. He marries and settles down. His uncle is so impressed by his personal growth that he rewards Donald with a good job, with great opportunities for advancement. He never misses a day of his Wellbutrin, and neither do I.